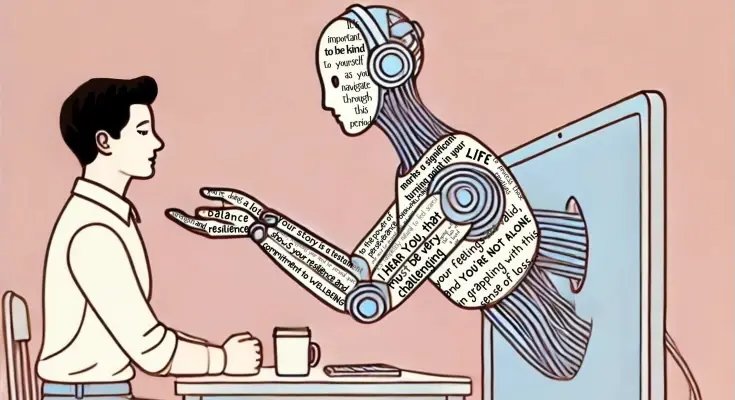

"I am aware it's a machine but it's super convenient and knows how to listen well whenever I need it," says Anna, a Ukrainian living in London. She is talking about her regular use of the premium version of ChatGPT, a chatbot powered by artificial intelligence.

What Anna – the BBC is not using her real name to protect her identity – finds particularly valuable isn't necessarily the AI's advice, but its ability to give her space for self-reflection.

"I have a history with it, so I can rely on it to always understand my issues and communicate with me in a way that suits me," she says. She is aware that this might seem odd to many people, including her friends and family, which is why she has asked to remain anonymous.

"I am aware it's a machine but it's super convenient and knows how to listen well whenever I need it," says Anna, a Ukrainian living in London. She is talking about her regular use of the premium version of ChatGPT, a chatbot powered by artificial intelligence.

What Anna – the BBC is not using her real name to protect her identity – finds particularly valuable isn't necessarily the AI's advice, but its ability to give her space for self-reflection.

"I have a history with it, so I can rely on it to always understand my issues and communicate with me in a way that suits me," she says. She is aware that this might seem odd to many people, including her friends and family, which is why she has asked to remain anonymous.

Read More